Handpainted sign for Super Bom tobacco. Photo by Nicholas Laughlin; 28 June, 2009

Topography: outside the main market, Waterkant

Saturday, August 29, 2009

Labels: sign, topography, waterkant

Notes: on bridges and meetings

Wednesday, August 26, 2009

By Christopher Cozier

Painting of Bollywood stars on a minibus in downtown Paramaribo, June 2009. Photo by Christopher Cozier

Initially, I was thinking of a theme around bridges, derived from the obvious: the two distinctive bridges, the Jules Wijdenbosch Bridge in Paramaribo and the Erasmus Bridge in Rotterdam. Both registered on my mind from the landscape on my first visits. For both cities, the bridges are significant to their stories and ambitions, reaching across not just water but communities and ways of understanding or experiencing where they are located. To me, this spoke about the role of visual practice and its dialogues--its potential to make connections between artists working in different but related circumstances.

In discussion with Marcel Pinas, Chandra van Binnendijk, Marieke Visser, Thomas Meijer, and Nicholas Laughlin, in what’s left of the iconic bar at the Torarica Hotel, the word “span” came up. Nicholas wanted to know whether, in local languages or Dutch, the word carried any further meanings or usages. I was still processing “ontmoeting”, the title of one of Soeki Irodikromo’s new paintings. It was a gestural work, with his distinctive and adventurous use of colour, which for him expressed a meeting point--an unlikely reckoning of people and ideas, but distinctive of the region. Like “span”, it conveyed the purpose or the idea.

Span is a word common to English, Dutch, and Sranan, via different etymologies, and with a range of meanings, nuances, implications. It is the space between two points, the means of crossing that space, a linking or pairing, a tension, a tightening, an excitement, a fullness, a reaching out.

What we in the Caribbean call Suriname is really Paramaribo, like Georgetown in Guyana: a coastal settlement with what appears to be an unfathomed “interior” and an ocean in front of it--or is it the other way around, with the ocean at its back? These settlements sit between two apparently infinite domains. It is a place between the Amazon and the Caribbean Sea ... a kind of entry point to something--something out-there or in-there that is not fully grasped.

On my first visit to Suriname, as I drove across the Jules Wijdenbosch Bridge, I felt that I was reaching inward and outward simultaneously. Ideas of the Caribbean, heavily shaped by island-ness, begin to diminish. This is the northern edge of a very large continent, and one of the starting points of exploration, conquest, and the ongoing formulation of the otherness of its climate, people, and landscape.

Why and how I see Suriname as a Caribbean place remains an open question. Is it because of the post-colonial, post-plantation dynamics of the transplanted people and architecture, or is it because the passing cars are thumping--reacting and agitating with Bollywood and dancehall beats?

Painting of dancehall star Sean Paul on a minibus in downtown Paramaribo, June 2009. Photo by Christopher Cozier

Like many who engage the Caribbean, for me the question Where is the Caribbean? often comes up. Because of emigration and expanding diasporic communities spread across Europe and the Americas, the Caribbean is best understood as a space rather than a specific location or place. Its permeable boundary may not delineate a particular territory.

This space is constantly shifting and expanding. The Caribbean is wherever its people find themselves and wherever people imagine the Caribbean. We are all now operating within this critical space. This is a challenging moment, as we all, not just in Europe, find ourselves in danger of slipping backwards into the despair of ethnic, cultural, and national territories or enclosures, not always for self-awareness but for vicious local squabbles over diminished resources.

The Caribbean in which Paramaribo resides or to which it reaches out or is sometimes narrated can also be seen as a critical space defined by certain questions about labour camps evolving into societies, about transplanted populations and early moments of Modernity defined by transnational labour sites and trade routes, and relations between competing European kingdoms transforming into nation states. By the struggle for its subjects from being property to being citizens--from being owned to owning. The Caribbean's relationship to Brazil or to Cayenne are all being processed.

Keti Koti cloth commemorating Emancipation, in a street vendor's tent in downtown Paramaribo, June 2009. Photo by Christopher Cozier

I do not think it is useful to the artists here for the Paramaribo SPAN project to be just a themeless national/cultural or ethnic list or inventory, with passport portraits, biographies, and a single work represented by a static image--a mere generic national culture calling card. There are too many books like that, and they do little to allow critical entry to the work and ideas of the artists.

The Rotterdam participants in the ArtRoPa project may be seen as belonging to a national discourse and an implied larger European and assumed “Internationalist” pedestal of old. Within this narrative, the Surinamese artists sit apart and within a fixed national, assumed cultural boundary and distanced placement--even those currently living and working in Europe. They are trapped within an overly defined representative role--a designation. Neither can see each other. We cannot really see them.

However, in response to today’s global questions, all of these assumptions mutually impose the same restricted readings. How can Paramaribo SPAN bring all of these participating artists into a critical context that does not make restrictive displays of their “difference” for consumption? How can we create a platform that unravels their common concerns as visual practitioners? To me, this can only be accomplished by looking at the work itself and by listening to the artists to see how these concerns may give shape to curatorial purpose--allowing a meeting point between curatorial and artistic intent.

Visiting artist Ravi Rajcoomar's studio, June 2009. From left: writer Nicholas Laughlin, Rajcoomar, curator Thomas Meijer zu Schlochtern. Photo by Christopher Cozier

For me, visiting these artists is also like an out-of-body experience, as most of the time I have been on the other side, being observed. Bobbing and weaving like a featherweight boxer contending with the scrutinising gaze--contending with the conditions of visibility.

In revisiting Soeki’s studio, I was thinking of a painting I had seen in 2005. One which the artist said was inspired by the aspirations of Carifesta, and through which he confidently investigated or navigated the neo-expressionism of late Modernity, but also aligned to similar ventures in the Antilles.

At the time, I was thinking of the works of Isaiah Boodhoo, Kenwyn Crichlow, and the Parboosinghs in Jamaica, for example--artists who pursued more open gestural and less schematised surfaces. In their work, ideas about rhythm, improvisation, and how colour functions in the Caribbean are investigated, but not exclusively in perceptual pursuits. There was also a conversation/speculation around sensibility and ethnicity. It was an optimistic dialogue about cultural crossovers and integration after electoral and national politics had failed us.

Soeki Irodikromo and Christopher Cozier discussing the painting Ontmoeting, June 2009. Photo by Thomas Meijer zu Schlochtern

Instead, visiting Soeki’s studio in June 2009, I encountered another recent and casually accomplished work called Ontmoeting.

Our conversation that day drifted from his recently stolen songbird, and its spectacular trilling (or “shining”, as we say in Trinidad), to his interest in and commitment to painting. Minding these vain and fickle tropical birds is a similar extended negotiative process, with its own form and aesthetic concerns--something like painting--which has fascinated me since my childhood, and which still seems to escape my full understanding. We were finding common ground.

Looking at the worlds that artists of Soeki’s generation try to reconcile, looking back into their ongoing moment--ongoing in that their concerns remain current each time one looks at or experiences the work--asks informative questions about our current location and ways of seeing.

Read the first set of Cozier's project notes here.

Labels: bridge, caribbean, cozier, notes, ontmoeting, soeki irodikromo

Seen: Suriname, Inside-Out, by Reshma Kirpalani

Monday, August 24, 2009

Photographer Reshma Kirpalani was born in Suriname but grew up in the United States. She is currently based in Florida. In 2007 she returned to Suriname and found, as she puts it, "a country full of cultural contradictions, swelling potential, woeful corruption, spiritualism, and spooky small towns with all-time high suicide rates."

The photographic project she started then is documented both on her blog Tatata and in a carefully curated selection of black-and-white images posted in a Flickr photoset, accompanied by a brief essay.

"I discovered Suriname," she writes. "No longer the resting my place of vague, childhood memories, this country is instead sometimes charming, sometimes alarming, always home. And yet, even as I enjoy citizenship status in this country, I am not wholly accepted as a 'local.' Rather, I am pointed to as the small American with the oversized camera....

"I no longer seek to 'sum-up' Suriname. Rather, I intend to explore this country just as it exists, at this point in time: on the eve of an election year, on the brink of progress, in the ebb and flow of inevitability."

See selections from Kirpalani's Suriname images here and here.

Labels: flickr, kirpalani, photography, seen

Diary: in Ellen Ligteringen's studio

Wednesday, August 19, 2009

By Nicholas Laughlin

27 June, 2009

Ellen Ligteringen works in a small bungalow in a quiet suburban neighbourhood north of central Paramaribo. The first sign that this is not simply a respectable middle-class house is the wooden rack in the paved driveway, hung with net sacks of what look like--

"Duck feathers," she says. "It's raining so much these days, they aren't drying properly."

Yet more sacks of feathers are hung around the enclosed verandah, and despite the excellent ventilation there is a definite fowlyard whiff in the air. Next to the kitchen door is a small washing machine, which Ligteringen uses to clean the feathers when they arrive from the duck farm.

Inside, the house is set up like a cross between a factory workshop and a science laboratory, with a long worktable down the middle of what probably used to be a living room. Steel shelves on either side are packed with boxes and plastic storage crates, neatly labelled. Lengths of wood and metal wire and an assortment of tools are neatly lined up on the table, alongside bowls and baskets of botanical specimens like seed pods and twigs. In one corner of the room is a heap of small green leaves, withered but not yet dried. On the kitchen counter, sealed glass jars are filled with a nearly opaque brown liquid, and what look like pieces of--

"Chicken skin. I'm experimenting with chicken leather."

Artist Ellen Ligteringen. Photo by Nicholas Laughlin

Of all the artists we have met on this trip to Paramaribo, Ligteringen is the one working with the oddest materials, and in the most open-ended, process-driven mode. Her current projects are investigative in an almost old-fashioned way. She seems fascinated with natural materials commonly thought to have little value--hence feathers and skin that are by-products of the poultry industry, and leaves, bark, and twigs from wild plants that would normally be considered "bush" needing to be cleared away.

Born in the Netherlands, but half-Surinamese (on her mother's side), Ligteringen moved to Suriname some years back. On the one hand, her work demonstrates a strong ecological consciousness. On the other, it seems to grapple with various cultural discomforts and shocks. She shows us a strange object that for want of a better word you might call sculpture: a pouch of brown chicken leather, roughly triangular in shape, filled with uncooked rice. It looks something like a pincushion, something like a piece of offal (a stomach?). "I call it Chicken and Rice," says Ligteringen, a wry reference to Suriname's national dish, which she says she got sick of eating over and over again. It is a weirdly fascinating object, both witty and rather morbid, simultaneously attracting and repulsing tactile investigation. You don't know if you want to touch it or not. (I didn't.)

In Ellen Ligteringen's studio. The triangular object to the left is Chicken and Rice. Beside it are samples of chicken leather. Photo by Nicholas Laughlin

She tells us how she taught herself to turn chicken skin into leather, researching the tanning process and devising a formula for a sort of tannin broth made from leaves and bark. Those murky jars on the kitchen counter are the next few batches of leather in progress. When she brings us cups of tea, the hot brown liquid exactly the same colour as the stuff in the tanning jars, I take a cautious sniff before I sip.

Next she shows us another sculptural object, a large dragonfly, a foot long, made from bent wire and scraps of wood. Fragments of bone, beetle wings, snakeskin, who knows what else, wait to be incorporated into the insect sculpture. I can't help thinking of Maria Sibylla Merian, the German artist-naturalist who spent two years in Suriname at the end of the 17th century, studying insect metamorphosis and recording the natural history of the country in vivid watercolours. Merian caught butterflies and moths in her kitchen garden, reared caterpillars in her parlour, and preserved small reptiles in casks of brandy.

Ligteringen's experiments are far removed from Merian's in intention, but her zestful curiosity is perhaps not so different, and her work similarly hovers at an unresolved intersection of art, science, and domestic craft. I am utterly fascinated, but can't say I entirely understand what she's looking for, or trying to make or prove or do.

By now she's moved on, and is telling us about her attempts to manufacture small batches of chocolate--she brings us yet another dark brown jar--and the cocoa trees she's planted outside, to eventually provide her raw materials. And the Surinamese Carib dancer she's been observing, fascinated by his working process. Her plans to use those duck feathers to stuff cushions of chicken leather....

Except the neighbours don't like her using her front verandah as a feather drying-room, she says as she shows us out. They don't like the smell. And maybe--she laughs--they wonder what she's really doing with them, and with all the other strange materials she collects. This small, sharp-eyed woman with her baskets of leaves and sacks of seed pods and bits of bone--is she an artist, or is she working some other kind of magic?

In Ellen Ligteringen's studio. Photo by Nicholas Laughlin

Labels: diary, laughlin, ligteringen, merian

Topography: Empire cinema, Fred Derbystraat

Monday, August 17, 2009

Labels: cinema, fred derbystraat, topography

Project: Arnold Schalks, Someni Tongo

Friday, August 14, 2009

Participants in Someni Tongo at the STVS studio, 22 November, 2008

Rotterdam-based Dutch artist Arnold Schalks is one of the participants in the ArtRoPa project, and the instigator of the journal De Surinoemer. In late 2008, during his artist's residency in Paramaribo, he created Someni Tongo, a community project that centres around poetry and recitation.

"Someni tongo" is a line from the poem "Wan Bon" ("One Tree") by the celebrated Surinamese poet and performer R. Dobru. Schalks interpreted "someni tongo"--"so many tongues"--as an imperative, and had Dobru's poem translated from Sranan into fifteen other languages spoken in Suriname: Arawak, Aukan, Chinese, English, Hindi, Modern Hebrew, Javanese, Kaliña, Lebanese, Dutch, Portugese, Saramaccan, Sarnami, Spanish, and Trio.

Premiere of Someni Tongo, broadcast on STVS

Schalks incorporated the sixteen translations in a five-part arrangement for a speaking choir. The translations are interwoven in such a way that each part sheds a different light on the poem's theme, "unity in diversity"/"diversity in unity". In each part, the sixteen voice-groups (one for each language) pronounce their versions of the poem simultaneously. The mixed choir, composed of 43 Surinamese, was conducted by Eldridge Zaandam and accompanied by the percussionist Ernie Wolf.

Someni Tongo was performed twice in Paramaribo: on Saturday, 22 November, 2008, at in the STVS studio, and on Saturday, 29 November 2008, in the Palmentuin. Schalks also produced a limited-edition DVD documenting the project in still and moving images.

"What I like about Dobru's poem is that it initially appears to be simple, something that must have been made with great ease. But if you look closer, you see a tremendously ingenious, sophisticated poem. I parsed it with respect, and tried to find just the proper visualisation of it. 'Someni tongo' was my starting point. Once you have so many languages, you also need people who speak those languages. And if these people finally line up, then 'someni prakseri', 'someni wiwiri', 'someni skin' but also 'wan pipel' suddenly become visible. You're looking at a sculpture. The perfect visualisation of the poem."

--Arnold Schalks, interviewed in November 2008 on the Skrifiman Taki ("Writer's Talk") radio programme, SRS-radio.

Someni Tongo performed at the Palmentuin, 29 November, 2008

For more information about Someni Tongo, including the names of the participants in the performance, see Arnold Schalks's website.

Conjunction: G-Star/WI STAR

Wednesday, August 12, 2009

By Nicholas Laughlin

This Is Not a G-Star / This Is Art, poster project by Shaudell Horton. Photographed in Paramaribo, 12 April, 2009

The rough, rudimentary, and raw characteristics of the brand allows G-Star to maintain its distinct and unorthodox style.... Futuristic and cautious. Far-reaching and experimental. Alternative and traditional. G-Star is about making eccentric combinations, and maintaining authenticity.

-- From the G-Star website.

G-Star RAW is a Dutch clothing brand whose "urban" style, often influenced by military apparel, is popular with young people in Western Europe--and in Suriname, where their boldly branded jeans, jackets, and t-shirts are a fixture in boutique windows along Domineestraat and other major shopping thoroughfares, competing for space with North American labels like Levis and inexpensive clothing imported from Brazil.

The brand doesn't seem to have caught on yet in the Anglophone Caribbean, and I'd never heard of G-Star until I noticed the poster above, pasted on a outdoor wall, in Paramaribo last April. I would have taken it for an advertisement, were it not for the location, just outside the Nola Hatterman Art Academy. A closer look revealed a caption suggesting this was an artist's project, but no name. Later I found out the poster was the work of Shaudell Horton, a student at Nola Hatterman, who made the piece during a 2008 workshop with a visiting instructor from the Gerrit Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam.

Visiting Paramaribo again in June, I thought of this poster one mid-morning when I ducked into a trendy downtown clothing shop to escape a sudden downpour. The women's section downstairs was packed with smartly dressed teenage shoppers. Upstairs was less hectic. As I browsed the racks, waiting for the rain to stop, I noticed a display of t-shirts with a distinctive graphic style. In varying combinations of red, green, yellow, black, and white--Suriname's national colours--they were boldly branded "WI STAR", in blocky text with the star-in-a-circle icon from the national flag.

Label on a WI STAR t-shirt, bought in Paramaribo in June 2009

Like Horton's poster, these t-shirts cheekily--and stylishly--comment not only on the shopping preferences of young Surinamese, but also on the notion of clothing and fashion as a badge of social identity--individual, communal, national, transnational. WI STAR means, of course, "our star" (perhaps with a hint of "we are stars"?), but to my Antillean eyes "WI" also suggests "West Indies", and the t-shirts are one more piece of evidence, conscious or otherwise, of Suriname's links to the Caribbean.

Needless to say, I bought one.

Graphic on a WI STAR t-shirt, bought in Paramaribo in June 2009

Labels: conjunction, fashion, g-star, laughlin, poster, shaundell horton, t-shirt, WI STAR

Notes: preliminary questions

Monday, August 10, 2009

By Christopher Cozier

Portraits of cultural heroes in a mural at the Zus and Zo Café on Grote Combeweg, Paramaribo, 16 April, 2009. Photo by Nicholas Laughlin

Inside the backdrop

Every time Fire Down Below, a Hollywood adventure set in Trinidad, comes on the Turner Classic Movie channel, I spend my time looking over and past the shoulders of those carrying the narrative into the setting or the backdrop. In the flux of co-stars and extras, the faces, the silhouettes passing in the background, the familiar trees, streets and buildings--the space--become for me a way of seeing not just fragments of past life in Trinidad but predicaments (operational space for all involved), rife with limitations and also opportunities. I have to have this special vision to block out or look around those foregrounded.

Often, when curatorial projects move from one site of operation to another, similar subject positions play out. How can I as a curator--an honorary curator?--of and moving within the Caribbean space make this shift? What other models can I arrive at? Will I act out the received and assumed role of universal knowing from the observation deck? Can I just simply look at the work, engage the artist, and possibly seek empathy? How does one enter the context--the critical space in and to which these artists are responding? How does one balance assumed similarities and differences? What is the meeting point?

Idealistically, in this blog I want to foreground the backdrop, and through the resulting interactive platform I hope to generate a fertile exchange around these questions towards transforming predicaments into mutually shared sovereign understandings.

Where is Suriname?

In my mind, I keep hearing these questions and others, as I move between various sites or situations of visual investigation. What do artists want, anywhere in the world, and especially in places like the Caribbean and in this case Suriname, here in the south of the region?

One quick answer would be: respectful and concerned critical and economic engagement of their ventures. Following on, there is also the ambition to creatively grapple with their craft and ways of seeing, as well as to investigate and alter the ongoing audience/public divide. One that is perhaps shaped by limited reading of visual practice and public expectations. There is also the current challenge of location--virtual and actual. In what narrative are these artists participating? What is the value of their endeavours?

Is the question of success simply about recognition or inclusion in the Netherlands, or participation in questions about the role or value of visual practice in the wider Caribbean, driven by developments in Havana, Kingston, Santo Domingo, or Port of Spain? Is it also about reaching out into even wider global dialogues?

Where is Suriname in this Caribbean narrative? In that of the Guianas? And, rarely asked, in that of the South American continent?

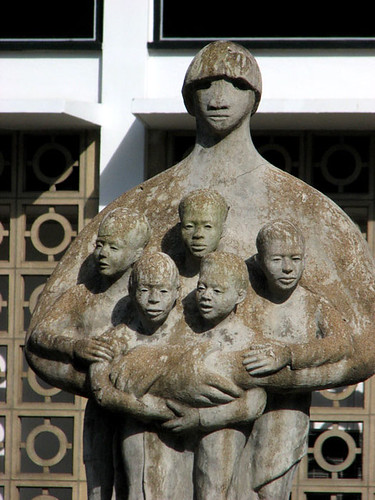

Mama Sranan sculpture outside the president's office in Paramaribo, 12 April, 2009. Photo by Nicholas Laughlin

Like everywhere else...

Like everywhere else in the region, Suriname's inventory of national pioneers and their adventures of self-discovery, their arguments with colonial authority, their local and foreign exile, their heroic departures and returns, may now seem distant and exclusive. Has it all played out, or just been reconfigured? Can we or have we already pressed the reset button, and are we navigating a new era? The dialogues of the mid-1990s leading up to the founding of Caribbean Contemporary Arts (CCA) in Port of Spain presented the question: is contemporary practice and its dialogues a rupture or a continuity? Is it both? What then is the critical value or the meaning of contemporary gestures?

A received historical formula...

Often the term “avant garde” still pops up. I have never used it, and I find it uncreative and inadequate in its implications, rooted in the stomping march of history, derived from the assertions of Modernism. A received historical formula may be imposed through this reading. One that obscures the critical architecture and trajectory of contemporary practice as it has come into being in the Caribbean. Contemporary practice may not be just an inventory of clearly delineated stylizations or forms, but a series of critical points of view that alter through varied and particular subject positions the way we (people of a certain experience or moment) critically engage our pasts and or possible futures.

This process reveals an ongoing series of current moments widening and expanding our visual understanding, rather than dismissing or violating past understandings. It renders the traditional boundaries, shaped by Modernism’s narratives, from received dichotomies--such as the self-taught versus the academician, the popular versus the formal, and all these terms--moot or of limited critical interest. It is not a dialogue of inclusion, but asking questions about critical understanding of the visual and its context in locations like Paramaribo. Where and how is visual expression happening and in dialogue with daily life and imaginings?

Painting on a minibus in downtown Paramaribo, 25 June, 2009. Photo by Nicholas Laughlin

What is its shape and form and its operational space?

Is it the painters of buses, shifting their symbolism to appeal to clientele either interested in Bollywood or dancehall, or those designing sound systems and “pimping” cars for the car shows? Is it those painting nostalgia, ethnicity, and nationhood or Amazonian flora and fauna aimed at the post-independence elites, expats and those yearning in the diaspora? Is it the Chinese photo studio downtown in which the waiting room displays meticulously arranged portraits of children of various ethnicities in pursuit of the diverse clientele that passes on the streets outside? Who has an image of the traditional angisa headkerchief whose style says “call me on my mobile”?

Somehow, the contemporary has all been framed as belligerence or the collapse of deference within post-independence culturalist territories.

There is a way in which standards, critical standards, formed from within or by the work itself produced within this experiential space, are denied their purpose and must then submit to random moments of encounter. A gaze that asserts a kind of value or purpose through acknowledgement or inclusion--therefore, may the conditions of visibility further obscure critical intent of the work?

Labels: cozier, curatorial, notes, questions

Topography: Feeling Shop, Maagdenstraat

Saturday, August 8, 2009

Labels: maagdenstraat, shop, topography

Elsewhere: August 2009 issue of De Surinoemer

Thursday, August 6, 2009

=

The latest issue of De Surinoemer, dated August 2009, has been released online. It features interviews (in Dutch) with two Surinamese artists currently participating in ArtRoPa residencies in Rotterdam: Roddney Tjon Poen Gie and Ravi Rajcoomar. Edited by Dutch artist Arnold Schalks and Surinamese artist Kurt Nahar, De Surinoemer is a free journal published at irregular intervals, documenting the ArtRoPa project. It is distributed in Paramaribo in a limited-edition printed version, and online in various formats (text, PDF, JPEG) at www.desurinoemer.net.

Translated excerpts from the artists' interviews in this edition of De Surinoemer will appear on Paramaribo SPAN in coming weeks.

Labels: de surinoemer, elsewhere, nahar, rajcoomar, schalks, tjon poen gie

Conversation: "You cannot eat from just one plate"

Wednesday, August 5, 2009

=

An interview with Kurt Nahar by Dutch artist Arnold Schalks; Paramaribo, 10 October, 2008. Both artists are involved in the ArtRoPa project, and Nahar participated a three-month residency in Rotterdam in 2008

[This is an abbreviated version of a conversation was first published, in Dutch, in De Surinoemer no. 5]

Dada in Susu (mixed media collage, 26 x 19 cm, 2009), by Kurt Nahar; photo by William Tsang, courtesy Readytex Art Gallery

Arnold Schalks: What were your expectations coming to Rotterdam?

Kurt Nahar: I went to Rotterdam with very high expectations. It is the dream of every artist to be selected for such a large project. To be recognised by someone on the other side of the ocean, after all these years of struggle with the work.

AS: Has your stay in Europe changed the way you look at Suriname?

KN: Yes, the possibilities I've seen in Europe constantly change the picture. If you live and work in just one place, you get into a vicious circle. The Internet is a possibility [for reaching out], but it is important to be near enough to see things, even smell them. You can only get so much from books or photographs....

The video and sound installations I saw in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam started me thinking. I do not need paint and a brush to express what I have inside. That insight is missing in Suriname. We've been told we have to sell, sell, sell. But art is the thing inside that you need to express. The sales will come anyway. If I want to present my concept in some other way, I have the right to do that, just as I've seen in Europe.

AS: What aspect of Suriname do you think is missing from Dutch society, and vice versa?

KN: In the Netherlands I missed Surinamese liveliness, freedom, and warmth.

You notice that when you come to Suriname. I don't need to tell you that. You've experienced it. Living in Rotterdam, that's what I thought was missing: that extra zest for life. You have everything in the Netherlands, but you still lack personality, individuality. We Surinamese lack your professionalism and industriousness. If we could merge....

Mona Lisa in Suriname (mixed media collage, 27 x 34 cm, 2008), by Kurt Nahar; photo by William Tsang, courtesy Readytex Art Gallery

AS: What do you think is the function of art?

KN: Art is, first, what is inside me bubbling to get out. I release it through art. Second, art is a voice for things at play in the community around me. I reflect these things in my work. Third, art is a means to get closer to the community. As an artist, you have a duty to educate. Through your work, you can show people what is right or wrong, and how to do things differently. Art reaches people better than a textbook.

AS: What is good art?

KN: For me, there is no such thing as good or bad art. An artwork is something I've considered at a particular moment, and it took that form. It's meaningless if someone buys an artwork for a sum of money, hangs it on a wall, and for ten years walks past it as though it were a mirror. The work means something if it touches the community. If I make an installation, within my context, about my own subjects and taboos, and someone stops me on the street five years later, saying, "Oh, you are the artist who made that strange thing with dolls and needles"--that for me is a confirmation that the work I made means something. I enjoy that ten times more than if someone buys a work and I have the money in my pocket, since that disappears in no time.

Untitled 2369 (mixed media collage, 27 x 34 cm, 2008), by Kurt Nahar; photo by William Tsang, courtesy Readytex Art Gallery

AS: Is your art Surinamese art?

KN: Previously, I was tempted to say my art is Surinamese art. My subjects came from my own environment. But the same issues are also relevant in other countries. That's why projects like ArtRoPa are so important....

I am an artist inspired by the things I see around me, and as a citizen of the world I change along with the time and spirit of the place where I currently am. Of course I still deal with Surinamese elements, but to say now that my work is Surinamese art--no. It is also foreign, Dutch, English. This is how I see it.

AS: But you can't deny your origins.

KN: I'll never do that. Suriname is my homeland, and I'll never exchange it for another. But as an artist you need to extend your limits. You cannot eat from just one plate. And I must tell the world about where I come from. That is my task. So, as an artist, I always mention my Surinamese nationality. I am a child of the Amazon, the bush. And then I come to the Netherlands, where the forests are smaller. I have tasted the possibilities of Europe, all the positive and negative things. I travel there to peck a grain of your knowledge. Also to be a bridge to the generations after me, so they can learn what I learned there.

But it works the other way too. You have also come here to learn from us. By talking about what drives us, we learn from each other. That's why I think my time in Rotterdam was the most fruitful period of my career.

AS: You are an omnivore. With great ease you seem to include everything in your work. Are there limits to your choices?

KN: No, I exclude nothing. Artists are strange people. We live in another world with another spirit. Something drives us. I am never ashamed of the voice that inspires me. When I'm out on the street, something tells me, "Pick that up!" And I pick it up. I don't care what people think. And then I put the thing, whatever it is, into my artwork....

AS: Is everyone an artist?

KN: An artist is someone with a free spirit who somehow gets a gift from above. I see it everywhere. It is not just visual art. You know how much appreciation I have for the newspaper vendors there on the streets, folding each newspaper in a certain way? That is a rhythm, a form of presentation. Or the mother in the kitchen, who with the little she has manages to fill your belly. That plate of food to me is a work of art.

Vision 1 (mixed media on hardboard, 60 x 60 cm, 2007), by Kurt Nahar; photo by William Tsang, courtesy Readytex Art Gallery

Labels: artropa, conversation, interview, nahar, schalks

Diary: meeting Roberto Tjon A Meeuw

Monday, August 3, 2009

=

By Marieke Visser

22 July, 2009

Roberto Tjon A Meeuw (born Paramaribo, 1969) is the first visual artist I interview for Paramaribo SPAN. He will be in Rotterdam from the end of July till October, as an artist in residence. I am familiar with his work, but have never really spoken with him about his art. He is self-educated, and definitely not mainstream. An independent.

I meet him just two days before he's off to the Netherlands. With the family: his wife Hester and his sons Idris and Sonny. Of course with his family, because that's what it's all about. "I am easily filled and overflowing with love", Roberto says. "Even awakening in the morning is Walhalla to me. I feel thankful because I have woken today, my wife is lying next to me, my kids are there."

The atmosphere in his colourful house, where we have our talk, is pleasant. All around us: art. By the children, by friends, by Tjon A Meeuw himself. And lots of records (he is a DJ too, DJ Prepmatic), lots of books. He is not pretentious--no intellectual highbrow conversations here. But the work which surrounds us speaks for itself. It is clearly influenced by graffiti and hiphop elements, never limited to a canvas in a regular frame. Pieces of window panes, broken furniture, old electricity poles: Tjon A Meeuw uses "garbage" as his medium. He literally starts from "scratch".

Roberto Tjon A Meeuw in his backyard, with one of his sculptures. Photo by Thomas Meijer zu Schlochtern

"Do you consider yourself an artist?" I ask him. "I am an interpreter," he says. "I translate the messages I receive from the universe any way I can: through the art I make, through the music I play. I am a mailman. And the message I bring is love, pure love. So yes: I am an artist who delivers the mail."

It sounds a bit hippie-ish maybe. But his mischieveous grin gives me the idea that he is for real. What sets Tjon A Meeuw apart, among other things of course, is that he is the first artist I've met participating in an exchange programme who is not talking in a grateful and humble tone about what he hopes to learn from this experience. No, Roberto Tjon A Meeuw is a man on a mission. He is going to get more ammo, to spread the word that a lot of good stuff is happening here in Suriname, and he's going to show the world just so.

"Shoot some flares, bomb da place, we gaan gewoon law!"--"we'll just go crazy!" And again, that smile. Yeah, he knows Rotterdam was bombarded during the Second World War, and that you should be very careful with the words you choose. And then I grin, thinking about the words he chose for one of his t-shirt prints: "pang pang".* High quality pieces of clothing, very stylish design, and words from the gutter. The mailman delivering his message.

* pang pang: Sranan term for female genitalia, often used as an insult

Tjon A Meeuw models one of his "pang pang" t-shirts; image courtesy Roberto Tjon A Meeuw

Labels: diary, tjon a meeuw, visser

Topography: corner of Domineestraat and Steenbakkerijstraat, outside the Hotel Krasnapolsky

Saturday, August 1, 2009

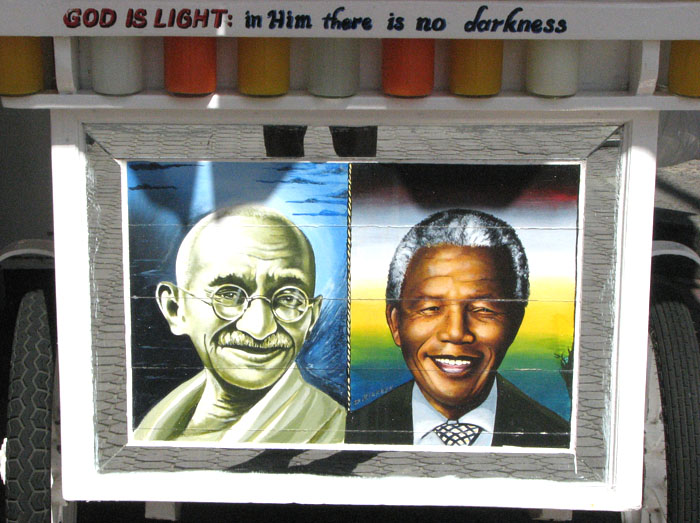

Wolly's ice cart, decorated with portraits of Mohandas Gandhi and Nelson Mandela. Photos by Nicholas Laughlin; 26 June, 2009

Labels: gandhi, ice cart, mandela, street painting, topography