By Christopher Cozier

Portraits of cultural heroes in a mural at the Zus and Zo Café on Grote Combeweg, Paramaribo, 16 April, 2009. Photo by Nicholas Laughlin

Inside the backdrop

Every time Fire Down Below, a Hollywood adventure set in Trinidad, comes on the Turner Classic Movie channel, I spend my time looking over and past the shoulders of those carrying the narrative into the setting or the backdrop. In the flux of co-stars and extras, the faces, the silhouettes passing in the background, the familiar trees, streets and buildings--the space--become for me a way of seeing not just fragments of past life in Trinidad but predicaments (operational space for all involved), rife with limitations and also opportunities. I have to have this special vision to block out or look around those foregrounded.

Often, when curatorial projects move from one site of operation to another, similar subject positions play out. How can I as a curator--an honorary curator?--of and moving within the Caribbean space make this shift? What other models can I arrive at? Will I act out the received and assumed role of universal knowing from the observation deck? Can I just simply look at the work, engage the artist, and possibly seek empathy? How does one enter the context--the critical space in and to which these artists are responding? How does one balance assumed similarities and differences? What is the meeting point?

Idealistically, in this blog I want to foreground the backdrop, and through the resulting interactive platform I hope to generate a fertile exchange around these questions towards transforming predicaments into mutually shared sovereign understandings.

Where is Suriname?

In my mind, I keep hearing these questions and others, as I move between various sites or situations of visual investigation. What do artists want, anywhere in the world, and especially in places like the Caribbean and in this case Suriname, here in the south of the region?

One quick answer would be: respectful and concerned critical and economic engagement of their ventures. Following on, there is also the ambition to creatively grapple with their craft and ways of seeing, as well as to investigate and alter the ongoing audience/public divide. One that is perhaps shaped by limited reading of visual practice and public expectations. There is also the current challenge of location--virtual and actual. In what narrative are these artists participating? What is the value of their endeavours?

Is the question of success simply about recognition or inclusion in the Netherlands, or participation in questions about the role or value of visual practice in the wider Caribbean, driven by developments in Havana, Kingston, Santo Domingo, or Port of Spain? Is it also about reaching out into even wider global dialogues?

Where is Suriname in this Caribbean narrative? In that of the Guianas? And, rarely asked, in that of the South American continent?

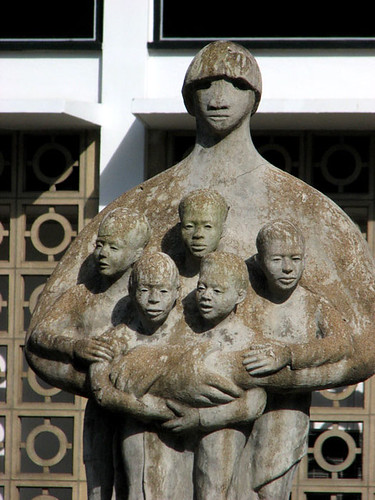

Mama Sranan sculpture outside the president's office in Paramaribo, 12 April, 2009. Photo by Nicholas Laughlin

Like everywhere else...

Like everywhere else in the region, Suriname's inventory of national pioneers and their adventures of self-discovery, their arguments with colonial authority, their local and foreign exile, their heroic departures and returns, may now seem distant and exclusive. Has it all played out, or just been reconfigured? Can we or have we already pressed the reset button, and are we navigating a new era? The dialogues of the mid-1990s leading up to the founding of Caribbean Contemporary Arts (CCA) in Port of Spain presented the question: is contemporary practice and its dialogues a rupture or a continuity? Is it both? What then is the critical value or the meaning of contemporary gestures?

A received historical formula...

Often the term “avant garde” still pops up. I have never used it, and I find it uncreative and inadequate in its implications, rooted in the stomping march of history, derived from the assertions of Modernism. A received historical formula may be imposed through this reading. One that obscures the critical architecture and trajectory of contemporary practice as it has come into being in the Caribbean. Contemporary practice may not be just an inventory of clearly delineated stylizations or forms, but a series of critical points of view that alter through varied and particular subject positions the way we (people of a certain experience or moment) critically engage our pasts and or possible futures.

This process reveals an ongoing series of current moments widening and expanding our visual understanding, rather than dismissing or violating past understandings. It renders the traditional boundaries, shaped by Modernism’s narratives, from received dichotomies--such as the self-taught versus the academician, the popular versus the formal, and all these terms--moot or of limited critical interest. It is not a dialogue of inclusion, but asking questions about critical understanding of the visual and its context in locations like Paramaribo. Where and how is visual expression happening and in dialogue with daily life and imaginings?

Painting on a minibus in downtown Paramaribo, 25 June, 2009. Photo by Nicholas Laughlin

What is its shape and form and its operational space?

Is it the painters of buses, shifting their symbolism to appeal to clientele either interested in Bollywood or dancehall, or those designing sound systems and “pimping” cars for the car shows? Is it those painting nostalgia, ethnicity, and nationhood or Amazonian flora and fauna aimed at the post-independence elites, expats and those yearning in the diaspora? Is it the Chinese photo studio downtown in which the waiting room displays meticulously arranged portraits of children of various ethnicities in pursuit of the diverse clientele that passes on the streets outside? Who has an image of the traditional angisa headkerchief whose style says “call me on my mobile”?

Somehow, the contemporary has all been framed as belligerence or the collapse of deference within post-independence culturalist territories.

There is a way in which standards, critical standards, formed from within or by the work itself produced within this experiential space, are denied their purpose and must then submit to random moments of encounter. A gaze that asserts a kind of value or purpose through acknowledgement or inclusion--therefore, may the conditions of visibility further obscure critical intent of the work?

Notes: preliminary questions

Monday, August 10, 2009

at 12:47 PM

Labels: cozier, curatorial, notes, questions

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comments:

A small, little-known country that penetrates few consciousnesses, even in its own region. That sums Surinam up pretty well. When I went there for my own research, back in the early nineties, the young woman at Council Travel, the company that arranged student travel, had never heard of it. "It's where Jimmy Smits father came from," I told her. "Oh!" she said brightly, and without real interest.

A couple of years later, when I was introduced to the faculty of my first real university job, in the hills of Kentucky, the dean of arts and sciences, having read the title of my dissertation, which included the words "the roots of post-colonial democracy in Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, and Surinam," informed my new colleagues that I had arrived fresh from research in the Caribbean and Africa.

My first contact with Surinam, however, came when I'd gone to Kingston to take the UWI scholarship exam in 1975. I'd stayed at the United Theological Centre, and the night before the exam started I'd wandered around and met a young white chap whose father was one of the instructors at UTC. In 1993, in Paramaribo, I was introduced to a white man of my age, who I was told had just returned to Surinam after completing his doctorate in sociology in the US. So, we got to talking, he mentioned having lived in Jamaica, and I blurted out "I know you!" It was indeed the same fellow I'd met eighteen years earlier, J. Marten Schalkwijk.

Post a Comment