Detail of Sri Irodikromo’s Ingiwinti

By Nicholas Laughlin

Sri Irodikromo’s Ingiwinti is a monumentally scaled batik panel, approximately thirty feet long by ten feet wide, dyed in vivid shades ranging from scarlet to crimson, and “embroidered” with dried rainforest vines and roots. For Paramaribo SPAN, it was installed outdoors, suspended from stout bamboo rods at the end of an avenue of palm trees. On the night of the exhibition opening, dramatically spotlit, this vertical apparition of gorgeous and glowing red served as a beacon, drawing visitors to the far end of the DSB Bank garden.

Ingiwinti on the opening night of the Paramaribo SPAN exhibition

But Ingiwinti might also be seen as another kind of beacon, drawing our attention to a mental space where cultural and spiritual traditions meet and negotiate. Its title refers to a series of rituals in which winti — Suriname’s traditional syncretic religion, drawing on the beliefs and practices of several West African peoples — adopts elements from (but is also adopted by) indigenous Amerindian peoples. The colour red is traditionally worn by celebrants of ingiwinti rituals. Irodikromo says the colour also refers to the seeds of the kuswe plant — called annatto, roucou, or achiote in other parts of Latin America and the Caribbean — used as a medicine, a cosmetic, a food dye. And the symbols and motifs patterning the cloth panel are borrowed from indigenous and Maroon art and the Afaka syllabary.

Irodikromo explains that she is usually unaware of the specific meanings and nuances of these symbols. “I make my own story,” she says. “I know that the symbols have no negative messages. They are all good signs.” But this isn’t a case of straightforward cultural appropriation, and Irodikromo does not use these motifs as a shortcut to some notion of cultural authenticity. Open about her position as an outsider to Maroon and Amerindian communities, she seems to be exploring the accessibility of elements of their visual and spiritual culture to members of other communities, both within and without Suriname. She questions rather than asserts, and respects the inscrutability of beliefs and ideas outside her own experience.

Irodikromo (left) dyeing the Ingiwinti fabric panels with the help of an assistant. Photos by Hedwig PLU De La Fuente

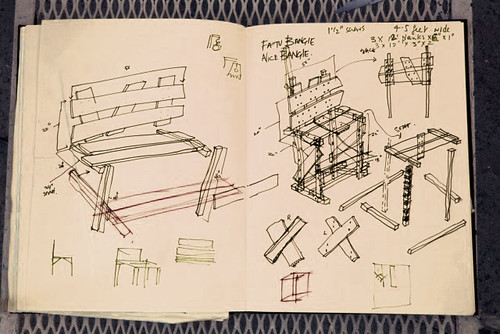

At the same time, the very medium of Ingiwinti creates another space of meeting and exchange. Batik is a technique of wax resist dyeing native to Indonesia and brought to Suriname by indentured Javanese immigrants, from whom Irodikromo is descended on her father’s side. In a recent conversation with artist Ellen Ligteringen, Irodikromo spoke of batik as a form of cultural preservation or recuperation:

Sri Irodikromo: I use batik on everything. I still am in the middle of experimenting.

Ellen Ligteringen: What is the essence of batik?

SI: Batik is an ancient technique. It comes from Indonesia. My roots are also from Indonesia, and that is why I work with batik.

Batik is actually saving colours. Fabric is covered with beeswax. For example, you have a white fabric, and you cover one section with beeswax, which remains white if you put the fabric in a dye bath.

EL: What other techniques play a role in your work?

SI: I not only use batik, I embroider, paint, and use grease on my canvases. I work with roots and twigs on the canvas. I use every technique I am able to work with. I see what is possible or not.

EL: You’ve worked a while in the Netherlands.

SI: I’ve done lithography and etchings.

EL: I see similarities. Etching and lithography are also about saving. You then work on a plate or a stone, but I see similarities with how you work on canvas.

The artist working on Ingiwinti with the help of her father, Soeki Irodikromo. Photos by Hedwig PLU De La Fuente

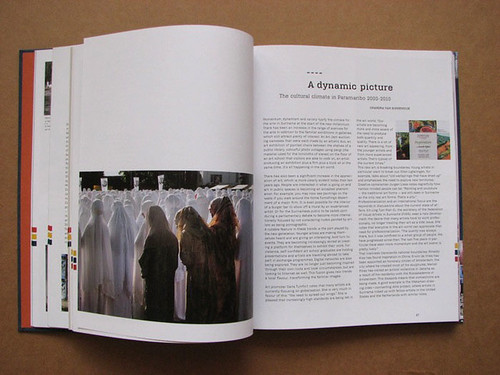

For an older generation of Surinamese (and Caribbean) artists — such as Soeki Irodikromo, Sri’s father — the combination of symbols and forms drawn from their country’s various ethnic communities was often a way of describing and asserting a national identity, of hypothesising if not celebrating an idea of national unity. In a work like Ingiwinti, Irodikromo seems more tentative, negotiating between the familiar and the strange in search of a position of understanding and accommodation. At the same time, its scale and powerful visual presence suggest that to be tentative is not necessarily to be vague or indecisive. Questions can be as powerful as declarations.

Photo by Hedwig PLU De La Fuente

Photo by Christopher Cozier

Installing Ingiwinti in the DSB Bank garden. Photo by Christopher Cozier