Draconian Switch is an art and design e-magazine published in Trinidad by Richard Rawlins with the collaboration of a group of artists, designers, and writers, many of whom work in the advertising industry. Each issue can be downloaded as a PDF, and the online archive also includes several one-off artists' publications.

Paramaribo SPAN curators Christopher Cozier and Thomas Meijer zu Schlochtern invited Rawlins to Suriname in late February 2010 to observe and participate in the opening events of the SPAN exhibition. The result is a special issue of Draconian Switch, which is now available for download.

Incorporating numerous images, works by the SPAN artists, and texts drawn from the SPAN blog, this special issue is Rawlins's personal creative response to Paramaribo SPAN, in the language of visual design. It offers another entry-point into the conversations provoked by the entire SPAN project.

The cover features examples of Rawlins's "Suriname alphabet", a series of images of letterforms collected around Paramaribo.

(Note: this issue of Draconian Switch includes streaming video, so it is best viewed in Adobe Acrobat Reader with a live Internet connection.)

Reading: SPAN issue of Draconian Switch

Thursday, April 1, 2010

Labels: draconian switch, rawlins, reading

Project: Ingiwinti, by Sri Irodikromo

Sunday, March 28, 2010

Detail of Sri Irodikromo’s Ingiwinti

By Nicholas Laughlin

Sri Irodikromo’s Ingiwinti is a monumentally scaled batik panel, approximately thirty feet long by ten feet wide, dyed in vivid shades ranging from scarlet to crimson, and “embroidered” with dried rainforest vines and roots. For Paramaribo SPAN, it was installed outdoors, suspended from stout bamboo rods at the end of an avenue of palm trees. On the night of the exhibition opening, dramatically spotlit, this vertical apparition of gorgeous and glowing red served as a beacon, drawing visitors to the far end of the DSB Bank garden.

Ingiwinti on the opening night of the Paramaribo SPAN exhibition

But Ingiwinti might also be seen as another kind of beacon, drawing our attention to a mental space where cultural and spiritual traditions meet and negotiate. Its title refers to a series of rituals in which winti — Suriname’s traditional syncretic religion, drawing on the beliefs and practices of several West African peoples — adopts elements from (but is also adopted by) indigenous Amerindian peoples. The colour red is traditionally worn by celebrants of ingiwinti rituals. Irodikromo says the colour also refers to the seeds of the kuswe plant — called annatto, roucou, or achiote in other parts of Latin America and the Caribbean — used as a medicine, a cosmetic, a food dye. And the symbols and motifs patterning the cloth panel are borrowed from indigenous and Maroon art and the Afaka syllabary.

Irodikromo explains that she is usually unaware of the specific meanings and nuances of these symbols. “I make my own story,” she says. “I know that the symbols have no negative messages. They are all good signs.” But this isn’t a case of straightforward cultural appropriation, and Irodikromo does not use these motifs as a shortcut to some notion of cultural authenticity. Open about her position as an outsider to Maroon and Amerindian communities, she seems to be exploring the accessibility of elements of their visual and spiritual culture to members of other communities, both within and without Suriname. She questions rather than asserts, and respects the inscrutability of beliefs and ideas outside her own experience.

Irodikromo (left) dyeing the Ingiwinti fabric panels with the help of an assistant. Photos by Hedwig PLU De La Fuente

At the same time, the very medium of Ingiwinti creates another space of meeting and exchange. Batik is a technique of wax resist dyeing native to Indonesia and brought to Suriname by indentured Javanese immigrants, from whom Irodikromo is descended on her father’s side. In a recent conversation with artist Ellen Ligteringen, Irodikromo spoke of batik as a form of cultural preservation or recuperation:

Sri Irodikromo: I use batik on everything. I still am in the middle of experimenting.

Ellen Ligteringen: What is the essence of batik?

SI: Batik is an ancient technique. It comes from Indonesia. My roots are also from Indonesia, and that is why I work with batik.

Batik is actually saving colours. Fabric is covered with beeswax. For example, you have a white fabric, and you cover one section with beeswax, which remains white if you put the fabric in a dye bath.

EL: What other techniques play a role in your work?

SI: I not only use batik, I embroider, paint, and use grease on my canvases. I work with roots and twigs on the canvas. I use every technique I am able to work with. I see what is possible or not.

EL: You’ve worked a while in the Netherlands.

SI: I’ve done lithography and etchings.

EL: I see similarities. Etching and lithography are also about saving. You then work on a plate or a stone, but I see similarities with how you work on canvas.

The artist working on Ingiwinti with the help of her father, Soeki Irodikromo. Photos by Hedwig PLU De La Fuente

For an older generation of Surinamese (and Caribbean) artists — such as Soeki Irodikromo, Sri’s father — the combination of symbols and forms drawn from their country’s various ethnic communities was often a way of describing and asserting a national identity, of hypothesising if not celebrating an idea of national unity. In a work like Ingiwinti, Irodikromo seems more tentative, negotiating between the familiar and the strange in search of a position of understanding and accommodation. At the same time, its scale and powerful visual presence suggest that to be tentative is not necessarily to be vague or indecisive. Questions can be as powerful as declarations.

Photo by Hedwig PLU De La Fuente

Photo by Christopher Cozier

Installing Ingiwinti in the DSB Bank garden. Photo by Christopher Cozier

Labels: batik, irodikromo, laughlin, project

Meanwhile: Richard Rawlins’s Alice Bangi

Tuesday, March 23, 2010

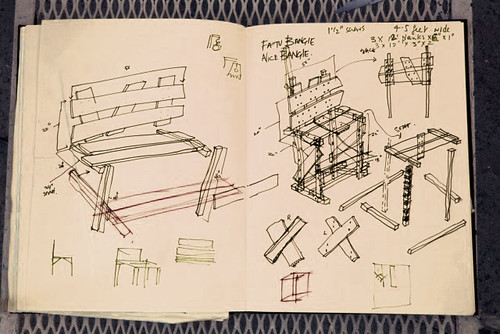

Richard Rawlins’s design sketches for the Alice Bangi

Artist and designer Richard Rawlins was a member of the Trinidadian contingent at the opening of the Paramaribo SPAN exhibition at the end of February. On his return to Trinidad, inspired by Roberto Tjon A Meeuw’s Fatu Bangi project, Rawlins designed and built his own version of a traditional Surinamese fatu bangi at Alice Yard, the arts space run by architect Sean Leonard in collaboration with Christopher Cozier and Nicholas Laughlin.

The Alice Bangi, now installed in Alice Yard's outdoor space, is decorated with stenciled graphics documenting various events and artists' projects from the past year.

Painted graphics on the Alice Bangi

Read Rawlins's notes on the project and see photos documenting the construction of the bangi at the Alice Yard blog.

(Rawlins is also the publisher of the e-magazine Draconian Switch, which covers art and design in Trinidad and the Caribbean. A special issue responding to and documenting Paramaribo SPAN will be published later this month.)

Labels: alice yard, fatu bangi, meanwhile, rawlins, tjon a meeuw, trinidad

Topography: walking fingers, Domineestraat

Monday, March 22, 2010

Sticker graphic from artist Jeroen Jongeleen’s project influenza/a little movement, on a shopfront in downtown Paramaribo, 24 February, 2010; photo by Nicholas Laughlin

Labels: domineestraat, graffiti, jongeleen, topography

Diary: return to Pikinslee

Wednesday, March 17, 2010

The Saamaka Kondë museum in Pikinslee

Karel Doing and Mels van Zutphen are artists based in Rotterdam, and participants in the ArtRoPa programme. During their residencies in Suriname, they both visited the village of Pikinslee, on the Upper Suriname River. Their time there inspired the work they showed in the Paramaribo SPAN exhibition.

After the exhibition opening in late February, both artists returned to Pikinslee to share their projects with the community there. They send the following notes about this visit.

The opening of Paramaribo SPAN was not the end of activities for us. We both worked on time-based art (a 16mm film and a video installation) in Upper Suriname, in a village called Pikinslee. The Maroons that live in Pikinslee have just completed building a museum to preserve the fast-changing and disappearing Saramaccan culture for the next generations. The village promises to develop into an important cultural centre in the interior of Suriname in the coming years. Due to the activities and collaboration of the villagers and Maroon diaspora in the Netherlands and Paramaribo, there is a particular openness in Pikinslee, although it is situated in a still isolated region.

We were both very eager to show the films we made on our earlier visit. With the help of Kens Libbarth and the local artists' group Totomboti, we organised an event for the inhabitants of the village.

Members of the audience at the screening in Pikinslee

On Wednesday 3 March the people came in large numbers and waited full of anticipation for the screening to start. Because of a lack of working sound equipment, the first film we screened was Djoeka, a Dutch travelogue from 1927, recently digitised by Eye Film Institute. This travelogue consists of extensive footage shot on the Suriname River, around Botopasi and Asidonhopo (close to Pikinslee). Besides a journey by dugout canoe, the film shows many activities like music, dance, food preparation, hairdressing, religious ceremonies, and portraits of people and architecture.

Looking back onto their own history proved to be very exciting for the audience. There was a lot of commentary, laughter, and discussion during and after the film. The audience was amazed that the colonials did not have outboard motors on their boats and had to paddle for weeks before reaching their destination. Also they were struck by the dancing styles depicted, very different from today's style. The main title and intertitles of the film were considered crude and badly informed, reflecting the arrogance of the Dutch editors. Also, the audience could see how different the river was before the Afobaka dam was built. Many other comments were lost in translation somewhere between Saramaccan, Dutch, Sranan, and English, the languages spoken by the assembled public.

An excerpt from Looking for Apoekoe (2010; 16-mm film, 13 minutes), by Karel Doing

The next day, a sound installation was set up, and the screening continued. The crowd was as big as the day before, and during the screening more and more people gathered. During Karel’s Looking for Apoekoe the audience sat quietly, softly commenting on the strange but still familiar images they saw. Afterwards some astonished comments were heard. Karel’s film is a mysterious trip circling around the bush-spirit Apoekoe, a lively, smart figure taking various shapes and with many special features.

Installation views of Man in Gold (2010; video loop, 20 minutes), by Mels van Zutphen, at the Paramaribo SPAN exhibition

Next was Mels’s film Man in Gold, a film version of the video installation screened in Paramaribo. It depicts the building of a korjaal (dugout canoe), the shipping of two big golden objects from Paramaribo upstream on the Suriname River, and a man with a golden suit on a moped. It was shot with the help of local canoe engineers and the people from the Totomboti foundation.

Berry, nephew of canoe builder Bernard, was very exited to see if anyone would recognise him as the man in the golden suit, made by his aunt Joney. Children laughed out loud on seeing canoe builder Alfred, whose face was covered with dust caused by the chainsaw. Etje Doekoe, an artist from Totomboti who saw a rough cut of the film a few months earlier during a visit to Rotterdam, asked Mels about a particular shot that he didn’t see in the final version: a palm tree waving in the wind. Mels was fascinated by the fact that Etje missed this shot and not the others of himself that didn’t make it. It’s not a problem, Etje said, I just liked the waving palm trees a lot....

Etje Doekoe in the Saamaka Kondë museum

The next day we were scheduled to go back to the city, but on the invitation of Totomboti we decided to stay one more day. It turned out to be the most relaxed day of our trip, and inevitably we started making plans for new projects in Suriname’s rich interior.

Rotterdam, 16 March, 2010

Elsewhere: March 2010 issue of Sranan Art Xposed

.

The March 2010 issue of the e-magazine Sranan Art Xposed — edited by Marieke Visser, Cassandra Gummels-Relyveld, and Priscilla Tosari, with the support of the Readytex Art Gallery — covers the Paramaribo SPAN exhibition, and also features an interview with artist Sri Irodikromo and notes on other recent exhibitions and artists’ projects. It is available in both English and Dutch editions, and can be downloaded from the Readytex website.

Labels: elsewhere, irodikromo, sax, sranan art xposed, visser

Diary: SPAN meets street

Monday, March 15, 2010

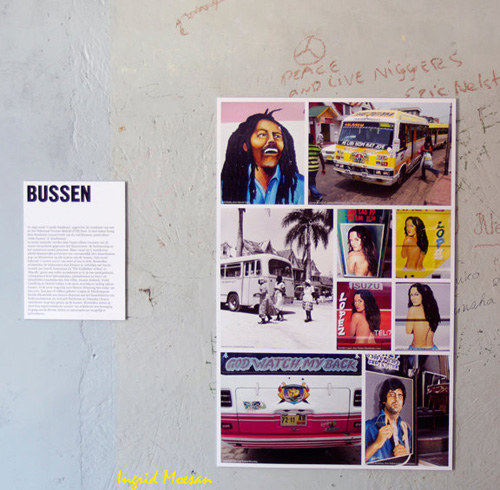

Images of bus paintings installed in the Schaafijs en Wilde Bussen exhibition; photo by Ingrid Moesan

Paul Faber, co-author of Schaafijs en Wilde Bussen: Straatkunst in Suriname, reports on an “Art Conversation” which brought together some Paramaribo SPAN artists and various street artists best known for their paintings on buses, walls, and shopfronts

Sunday evening, 7 March, 7 pm. Location: the garden of DSB Bank in Paramaribo. Inside and outside the central pavilion the works of the SPAN artists have found their own environment. Tonight the exhibition receives some special guests, a group of painters who make their living by painting buses and walls.

These painters rarely visit art exhibitions. They are here by invitation, because they created works that will be presented in an exhibition of their own, Schaafijs en Wilde Bussen, at Fort Nieuw Amsterdam. Sirano Zalman gives a guided tour for the street artists and other visitors. He shows the works, gives explanations, introduces other participating artists, such as George Struikelblok.

At 7.30 the crowd gathers in the back garden near Roberto Tjon A Meeuw's Fatu Bangi, a nice piece of wooden art-furniture, in front of a big clump of bamboo. About seventy people are present: the artists from both exhibitions, other interested artists, and art lovers. Magnificent palm tress and flowering bushes illuminated by hundreds of lights form a wonderful setting.

Images of painted shaved-ice carts in the Schaafijs en Wilde Bussen exhibition; photo by Ingrid Moesan

Karin Lachmising leads the conversation that unfolds over the next hour. Can you have a meaningful conversation between seventy people? Amazingly, the answer is an outright yes. The underlying question of this conversation is to discover how these two groups relate to each other. They obviously move in different circles, hardly know each other, and their jobs are structured in different ways. On the other hand, they are all “visual workers”, as someone puts it, and are dedicated to their work: how do they see each other’s work and (how) can they learn from each other?

The conversation, moving from one artist to another, touches in a natural and respectful way on all relevant issues. One of these is the message of the work. Some of the SPAN artworks deal with complex issues like pollution of the environment, suicide, and orphans. The commentary given during the tour helps a lot to explain the thoughts behind them, Ghalied Khodabaks says. The SPAN artists were obviously involved in what they wanted to say. But, as several discussants state, the street artists have their message too, more specified and narrow, but very clear at the same time. The bus painters concentrate on stars and heroes, emblems of beauty, to attract people. The painters of advertisements depict all kinds of products, like tomatoes or beer, in a way that makes the onlooker very thirsty indeed. It is the art of seduction, someone suggests.

The origin of this difference in the character of the message can be found in the relation with the commission. As André Sontosoemarto explains, the street artists have to deal with the clients, often companies, who order the paintings, and have specific requirements. The freedom of choice is limited for the painters, but not nil. The margin shows in the continuous innovation and development of ideas, techniques, and motifs.

It depends also on the artist's reputation. The bus painters like Ramon Bruyning and the Khodabaks brothers are known for the quality of their work and often get a free hand in the choice of motifs. Sirano admires their skills: how did you learn to paint so well, he asks. André explains there is hardly proper schooling in advertisement painting. Ideas to do something about this are presented on the spot. The bus painters are largely self-taught. They learned their art by using their eyes and practising with their hands, over and over again. Their standard is exceptionally high, also by international standards. Another interesting difference comes to light: the stage and the audience. “The whole city is our exhibition hall!” the street painters state proudly.

Soeki Irodikromo looks at one of the specially commissioned paintings; photo by Ingrid Moesan

At this point, the input of several painters of the older generation is enlightening. René Tosari, Winston van der Bok, John Djojo, and Steve Ammersingh were part of the artists’ collective Waka Tjopu, founded in the early 1980s. They relate the discussion of tonight to the objectives and ideals of then. Waka Tjopu brought art into the street, went for direct communication, painted large billboards, and avoided the use of the word “art”.

These stories link tonight’s conversation with a broader and deeper tradition in the Surinamese world of “visual workers”. A passionate speech by grand old man Soeki Irodikromo, whose daughter Sri participates in Paramaribo SPAN, rounds up this highly interesting evening. He implores people to continue this exchange, suggested that the painters leave some permanent mark in Fort Nieuw Amsterdam.

Tonight the street artists were confronted with a number of new ideas and possibilities, but also with respect and appreciation from new-found colleagues. Next Friday a nicely painted bus will leave from the Paramaribo SPAN exhibition venue for Fort Nieuw Amsterdam and the opening of Schaafijs en Wilde Bussen. After a quick family meeting, the Khodabaks brothers announce that they will provide the bus, which is bound to be a high-class example of their Bollywood style. It is a nice thought to be able to travel inside an artwork to an opening.

Images of wall paintings in the Schaafijs en Wilde Bussen exhibition; photo by Ingrid Moesan

Schaafijs en Wilde Bussen, an exhibition of Surinamese street art (including specially commissioned works) runs from 13 March to 2 May in the Open Air Museum of Fort Nieuw Amsterdam in the Commewijne district.

Labels: diary, faber, fort nieuw amsterdam, minibus, soeki irodikromo, street painting

Topography: minibus, Steenbakkerijstraat

Friday, March 12, 2010

Painting on a minibus waiting to collect passengers in downtown Paramaribo. Photo by Nicholas Laughlin; 24 February, 2010.

The painting is a portrait of Desi Bouterse, leader of the military regime that ruled Suriname after the 1980 coup, responsible for the December Murders in 1982 and the Moiwana Massacre in 1986. In 1999 Bouterse was convicted in absentia in the Netherlands for cocaine trafficking, but Surinamese law protects him from extradition.

He remains politically active and popular with some Surinamese, as this painting suggests. “Basi joeroe” is Sranan for “Boss’s time”.

Labels: minibus, street painting, topography

Reading: “Shaved Ice and Wild Buses”

Thursday, March 11, 2010

Jamaican dancehall star Sean Paul painted on a minibus in Paramaribo, June 2009; photo by Christopher Cozier

By Chandra van Binnendijk

[Adapted from an essay in Schaafijs en Wilde Bussen: Straatkunst in Suriname, by Chandra van Binnendijk, Paul Faber, and Tammo Schuringa, published in March 2010 by KIT Publishers]

One does not have eyes enough when making a trip through Paramaribo. Not only because of the people, the market, the nature, and the buildings. Anyone who pays attention will see that the city streets are filled with fine paintings. Inventive and funny images painted with great skill can be found on a small scale, such as on the fuel-tank covers of buses, but also on a gigantic scale, whereby entire buildings are covered with hyper-realistic advertisement-paintings. Seemingly real drops of water hang on the walls, as if the city is sweating due to the ever-present heat. How to quench the permanent thirst becomes immediately clear through the adjacent painted drink label.

Anyone who hangs around on a street corner for fifteen minutes will see a colourful parade of movie stars and celebrated singers and musicians passing by. The supreme Bollywood star Amitabh Bachchan passes by in five or six different film roles, alternating with Bob Marley. 2Pac looks at you with piercing eyes; Britney Spears gives you a provocative gaze that asks: would you like to drive with me, in this bus? On Johnny Sordam’s shaved-ice cart on Domineestraat, the two greatest peace apostles of the twentieth century, Gandhi and Mandela, stand fraternally next to each other, as if indicating that quenching one’s thirst is important, but not the most ponderous issue in the world.

What these forms of street art all have in common is that they are hand-painted with great care, and that the makers are unknown to the general public. The work of these painters does not hang in a museum. The street is their museum. They do not see themselves so much as artists, but in a way as advertisement painters.

Minibus, Paramaribo, June 2009; photo by Nicholas Laughlin

This kind of street art has not always existed in Paramaribo. The first scenes painted on buses begin to appear in the early 1970s, as additions to fixed information such as “Route 7, 15 passengers”. These images, portraits, and decorations give each bus a certain accent, ensuring that it stands out, drawing the attention of clients. The first bus painter, Eric Gilles, created highly imaginative scenes which have unfortunately not been preserved in photographs. After Gilles came a few others, such as Dennis Riebeek, Waldi Landburg, and Gerold Lobles. They painted large colourful names of buses such as MAGIC and MUSIC MACHINE, hot women, and internationally famous stars.

These artists all left for the Netherlands in 1990. Ramon Bruyning, an assistent to Lobles, managed their legacy and thereafter built up his own practice. He has worked on a great many of the buses which drive around today, which can be recognised by the motif of a symmetrical medal with a portrait in the middle, and Afro-American music stars. During the mid 1990s a second group of painters entered the flourishing bus-painting sector, led by the brothers Nishar and Johnny Khodabaks. Their repertoire consists mainly of film stars out of the Bollywood film industry, and has become the favourite of many bus owners.

The painting of shaved-ice carts began in the mid 1980s, when the number of ice-carts had a turbulent growth. The carts became bigger, they acquired roofs, and they were decorated in highly imaginative ways — some of them by the owners themselves, and others by the professional bus painters such as Lobles, Riebeek, and Bruyning. The peak is now past, but a number of shaved-ice carts still indicate how varied and attractive they once were.

Painted advertisements on the wall of a small grocery outside Paramaribo, June 2009; photo by Nicholas Laughlin

Advertisement painting is older than the moveable paintings on buses and carts. It began to conquer its place in the street scene after World War II, following the American example. The logos of international brand names such as Coca-Cola and Bata were faithfully copied, gradually joined by local brand names such as Black Cat and Parbo. Now giant advertisements and detailed reproductions of sweets and shining cars appear on walls and billboards. The walls of supermarkets are totally painted with cans of red beans or sardines.

In the last few years the paintings have increased both in size and in realism. A style of shop-painting has started in which the building is overgrown with advertisement. More and more the designs are prepared on computers, but the execution is still done by hand. Painters such as André Sontosoemarto and Hendry Singoredjo prepare the work and supervise different crews of painters, who tirelessly enlarge the design, covering even the bars of shutters and windows.

All these forms of painting find themselves places next to each other, and intermingle. “A bus is a bus, a billboard is a billboard,” says Sontosoemarto, and most of the painters stick to their particular area, but once in a while a crossover does take place.

Schaafijs en Wilde Bussen, an exhibition of Surinamese street art (including specially commissioned works) opens on Friday 12 March, 2010, in the Open Air Museum of Fort Nieuw Amsterdam in the Commewijne district.

The exhibition is open to the public from March 13 to May 2.

Tuesday-Friday, 9 am to 5 pm.

Saturday and Sunday (and on all holidays), 10 am to 6 pm.

Closed on Mondays.

Portrait of Paramaribo, by George Struikelblok, was created for The One Minutes project and is nominated for The One Minutes Awards 2009

Labels: advertising, minibus, reading, street painting, struikelblok, van binnendijk

Project: Een Lekkers, by Ellen Ligteringen

Monday, March 8, 2010

An unidentified visitor to the SPAN exhibition reacts to Ellen Ligteringen's chocolate

By Nicholas Laughlin

Ellen Ligteringen's Een Lekkers project occupies two small rooms adjacent to the kitchen in the DSB Bank gardenhouse, the main SPAN exhibition venue. In the scullery, she has set up a gedachtentafel, or "table of thoughts", a sort of recreation in miniature of her studio, displaying the weird objects she makes from chicken leather. In the small pantry next door is a makeshift confectionary shop, with chocolate bonbons — concocted by Ligteringen, with cocoa she harvested herself — displayed in a refrigerated glass case.

Visitors to the exhibition are invited to sit down, taste Ligteringen's chocolates, and register their reactions via a special questionnaire. Small digital cameras mounted on four sides of the room record their facial expressions and body language. An audio recording in the reassuring voice of Odette de Miranda — one of Suriname's best-known radio announcers — explains the process to the wary. The project is documented on Ligteringen's website, Tan Bun.

Like George Struikelblok's Groei — a sculptural enclosure in which he is rearing two hundred chickens — and Pierre Bong A Jan's live tattooing session on the opening night of the exhibition, Ligteringen's project involves an installation of objects and an element of public performance, but it is also a process of investigation. She calls it research, and takes the whole thing seriously enough to have recruited the help of a professional psychologist in drafting the questionnaire to which her audience is subjected.

President Ronald Venetiaan of Suriname prepares to taste one of Ligteringen's chocolates on the opening night of the exhibition. Image captured by one of the video cameras installed by the artist and used with her permission

The chocolate is made from pure cocoa, cream, and sugar, but the proportions change in each batch. One day the bonbons are luxuriously rich, the next day so bitter they hardly taste like chocolate at all. The artist is genuinely interested in what her visitors think of the confectionary, but the chocolate is also, she explains, a way of catching her audience off guard. "Lekkers" is the Dutch word for a tasty treat, but in Surinamese usage it also refers to a kickback, a payoff, an illicit exchange to help sweeten a deal. Interspersed among queries about flavour and texture, Ligteringen slyly poses subtle questions to gauge her visitors' thoughts about this other kind of "lekkers": Bent u al in de ja-mood? "Are you in the yes-mood?" Hoe krijg ik u in de ja-mood? "How do I get you in the yes-mood?" "Does my taste threaten you? Should I keep my mouth shut?"

"I want to play with habits," Ligteringen says. "I'm not in the phase of giving answers or conclusions. It's more like an inventory, descriptive research."

This open-endedness is a challenge to many visitors' notions of the acceptable forms and purposes of an artwork, and is also Ligteringen's response to what she calls the "CV parade" of the Dutch art world. "Sometimes I work as an artist, sometimes not," she explained in an interview with Marieke Visser in 2009. "I want to give myself the freedom to work outside that domain." Een Lekkers straddles that ambivalence. "It is not totally clear that I'm part of the SPAN exhibition," she says. "Visitors are surprised on entering that it is an art project." Indeed, on the opening night, some who failed to notice the explanatory wall label assumed Ligteringen was one of the caterers. President Ronald Venetiaan, touring the exhibition, was sufficiently impressed by the chocolates to ask whether Ligteringen had considered export.

"I know exactly what I will do after the exhibition," she says. "I will start my little skratishop [Sranan for chocolate shop] at the Sunday market, next to a friend who is telling you the future. If you cannot handle your future you can eat a chocolate. I will expand the performance in a longer timeframe."

Elvira Rijsdijk, art critic for De Ware Tijd, tastes Ligteringen's chocolate

Labels: chocolate, ligteringen, performance, project

Diary: looking for the red lights

Friday, March 5, 2010

A young woman poses with Ken Doorson’s Tipple Box on Van Sommelsdijckstraat, 26 February, 2010; photo by Richard Rawlins

By Nicholas Laughlin

26 February, 2010

Ken Doorson’s Tipple Box project is a series of three-sided red plexiglass boxes — illuminated from within and etched with the suggestive silhouettes of women — intended to be installed on the streets of Paramaribo. A motion sensor atop each box triggers the internal light as pedestrians or cars pass by, alerting both ordinary passers-by and those with less innocent intentions that they have entered one of the city’s red-light districts.

On the opening night of the Paramaribo SPAN exhibition, one of the Tipple Boxes was nestled rather incongruously in a grove of flowering shrubs in the DSB Bank garden, its red glow ceaselessly activated by the crowd of wine-sipping and hors d’oeuvre-nibbling guests. Near midnight, as the party wound down, a few of us decided to search out a companion box we knew was installed on one of the streets north of the Palmentuin. As we strolled through the neighbourhood, we were almost run over by an SUV full of determined-looking men, making a U-turn in the street to pull up next to a scantily clad young woman.

The Tipple Box on Van Sommelsdijckstraat, outside a nondescript commercial building; photo by Nicholas Laughlin

We found the Tipple Box on Van Sommelsdijckstraat, a block from the Torarica Hotel. On a corner outside an anonymous commercial building, it unexpectedly blended in with the illuminated signs for bars and nightclubs further down the strip. Doorson was DJing in a small bar just across the street. We stopped for a drink, and sat at a table outdoors, where we could keep an eye on the box and note the reactions of pedestrians.

Most kept their distance, perhaps wondering what it was advertising. But one young woman — dressed for a night out and accompanied by an older companion who could have been her mother or aunt — was intrigued. She stopped, stared, then tried to imitate the pose of the silhouette on the box: handbag over the arm just so, hand raised to caress her hair, weight shifted to her right leg. She was happy to be photographed, and gave us the name of the nightclub she was heading to.

SUVs cruised past.

Another view of the Tipple Box on Van Sommelsdijckstraat; photo by Richard Rawlins

Labels: diary, doorson, installation, laughlin

Elsewhere: February 2010 issue of Town

Wednesday, March 3, 2010

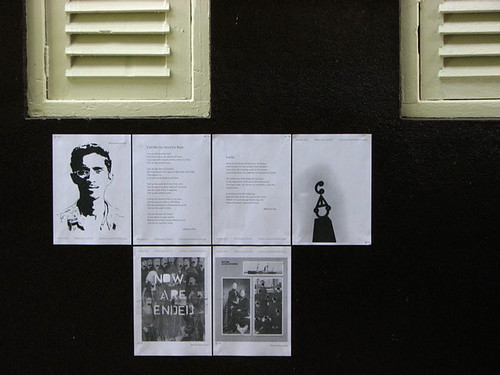

Broadsides from the third issue of Town posted in the DSB Bank garden, the main Paramaribo SPAN exhibition venue, 26 February, 2010

Town is a magazine of literature and art based in Port of Spain, Trinidad, and launched in October 2009. Co-edited by SPAN blog editor Nicholas Laughlin with writers Vahni Capildeo and Anu Lakhan, Town publishes poems, very short prose, and artists' images in two formats: on paper, in broadside editions posted in public locations; and online.

The third issue of Town, dated February 2010, engages with the Paramaribo SPAN project. The editors write:

“This issue of Town is also a sort of bridge, or the fragments of a possible bridge of imagination and understanding. It connects poems by a writer from Guyana, Suriname’s neighbour to the west; images by a Dutch artist of Surinamese ancestry, which reflect on the ironies of colonial history; a self-portrait by a young Surinamese artist, a work of both self-representation and self-assertion; and a deliberately mysterious photograph of the monument memorialising one of the most tragic events in Suriname’s recent history. The three Afaka characters atop the Moiwana Monument spell out ‘Kibii Wi’: Sranan for ‘Protect Us’: a hope, a wish, a lamentation, a charm, a song.”

Town issue 3, February 2010

The magazine was officially published on 26 February, the day of the Paramaribo SPAN opening, when Town broadsides quietly appeared at the exhibition venue, the DSB Bank garden, and also on walls and fences around Paramaribo. Broadsides will also be posted around Port of Spain, making another bridge between the two cities.

See the contents of this issue of Town online here. Readers can also download PDFs of the broadsides to make their own physical copies and post them anywhere in the world.

Town issue three, posted alongside party posters in Paramaribo...

... and next to a street painting by Dutch artist Jeroen Jongeleen

Reading: Paramaribo SPAN: Contemporary Art in Suriname

Tuesday, March 2, 2010

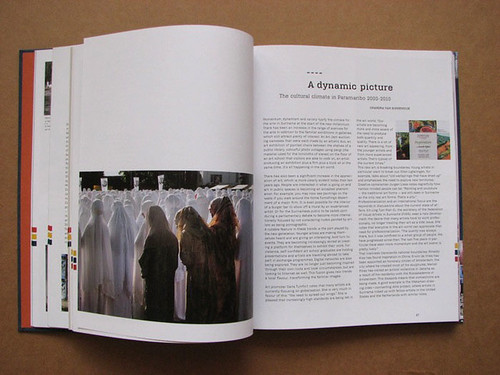

Spread from the English edition of the Paramaribo SPAN book, launched on 26 February

The Paramaribo SPAN project has three formal platforms, distinct but interconnected: this blog; the exhibition which runs from 26 February to 14 March; and the book Paramaribo SPAN: Contemporary Art in Suriname/Hedendaagse Beeldende Kunst in Suriname/Arte Contemporânea do Suriname, launched at the SPAN opening last week.

Edited by Thomas Meijer zu Schlochtern and Christopher Cozier, and published in three language editions (English, Dutch, and Portuguese) by KIT Publishers, Paramaribo SPAN is not a catalogue of the exhibition, though it features most of the artists participating in the show. Rather, in Meijer's words, it asks "where do the visual arts stand in Suriname in 2010 and what are the prospects for the future?" The book tackles this complicated question from multiple angles: biographies of individual artists, critical essays and surveys of recent developments by members of the SPAN project team, and documentation of the exchanges instigated by the ArtRoPa initiative.

Cover of the Dutch edition

Contributing writers include Meijer, Cozier, SPAN writers Chandra van Binnendijk and Marieke Visser, SPAN blog editor Nicholas Laughlin, Siebe Thissen of the Centrum Beeldende Kunst, artist Arnold Schalks, and journalists Fred de Vries and Liesbeth Babel. The book is supported by DSB Bank in commemoration of its 145th anniversary. For more information, see the KIT Publishers website.

Spread from the English edition

Labels: book, cozier, meijer zu schlochtern, reading

Opening night

Friday, February 26, 2010

Artist Sunil Puljuhn assists with the installation of Sri Irodikromo's Ingiwinti in the DSB garden; photo by Christopher Cozier

The Paramaribo SPAN exhibition opens at 7.30 pm this evening in the grounds of De Surinaamsche Bank's headquarters on Henck Arron Straat.

Artists Dhiradj Ramsamoedj and Ken Doorson in the DSB garden; photo by Christopher Cozier

Artist Karel Doing helps Sri Irodikromo during the installation of her Ingiwinti; photo by Christopher Cozier

Programme: Readytex Art Gallery “art fatu”

Thursday, February 25, 2010

Readytex director Monique Nouhchaia Sookdewsing talks to SPAN co-curator Christopher Cozier

Founded in 1993 by Monique Nouhchaia Sookdewsing, the Readytex Art Gallery in downtown Paramaribo is Suriname's leading commercial gallery. Many of the artists participating in the SPAN project — including Sri Irodikromo, Kurt Nahar, Marcel Pinas, Dhiradj Ramsamoedj, George Struikelblok, Roddney Tjon Poen Gie, and Jhunry Udenhout — show their work at Readytex or are represented by the gallery. As SPAN co-curator Christopher Cozier remarks, Readytex — on the second floor of a large commercial building on Maagdenstraat, also occupied by other branches of Nouchaia's family business — is an obligatory stop on Suriname's art circuit.

The programme of activities on the Paramaribo SPAN opening weekend includes several events outside the main exhibition venue at the DSB headquarters, all intended to broaden SPAN's conversation about the contemporary art scene in Suriname. On Saturday 27 February at 10 a.m., the Readytex Art Gallery will host an art "fatu" — an informal gathering — for the participating artists and organisers, visiting critics and curators, and other invited guests. Works by a range of contemporary Surinamese artists will be on display, and Nouhchaia will discuss plans for the new cultural centre she will open in March 2010.

Diary: three days to the opening

Tuesday, February 23, 2010

Detail of Ravi Rajcoomar's SPAN installation

With three days remaining until the opening of the Paramaribo SPAN exhibition, all the members of the SPAN curatorial and organising team are now in Paramaribo, and installation of the artists' works is almost complete at the main exhibition venue, the DSB garden.

Roddney Tjon Poen Gie working on his installation at the DSB garden. His project is a collaboration with photographer Sirano Zalman

The former director's villa and extensive grounds behind De Surinaamsche Bank's headquarters provide numerous indoor and outdoor spaces for works by twenty-nine Surinamese and Dutch artists, some of them created specifically for these sites. On opening night, Friday 26 February, the DSB garden will be illuminated by thousands of lights as guests encounter works including painting, photography, sculpture, installation, video, and several performance projects.

Sri Irodikromo installing her work in the DSB garden

Sunil Puljhun helps install Irodikromo's work

Labels: diary, irodikromo, puljhun, rajcoomar, tjon poen gie

Notes: on monuments and moments

Friday, February 19, 2010

By Christopher Cozier

Kurt Nahar’s 8 Dec 1982 installation at Fort Zeelandia; photo by Christopher Cozier

Often when I think of monuments in the Caribbean I think only of the commemoration of historically remote events, and most of the time in a passive and almost indifferent way. We think of a lost moment and of the attempt to preserve or project its value. These questions have been with me since my first visits to Paramaribo, observing the projects of artists Marcel Pinas and Kurt Nahar. There are so many commemorative statues and structures in this city. Somehow they seem to reduce rather than to expand or ignite curiosity. They just fit in, and the snow-cone cart, concert poster, or bus decoration seems to register more definitively or assertively on my mind. As in many other Caribbean locations, there remains a tension between formal and informal markers as you move around Paramaribo.

Concert poster, Paramaribo; photo by Christopher Cozier

Kurt Nahar’s project at Fort Zeelandia, 8 Dec 1982, refers to the date of what are called the December Killings. Fifteen people — trade unionists, journalists, academics, and soldiers — known to be opposed to the government, were rounded up, interrogated, tortured, and killed in this fort.

Marcel Pinas’s Moiwana monument commemorates the November 1986 massacre of over thirty men, women, and children during Suriname's civil war, at the actual site of the tragedy on the road between Moengo and Albina. This was the home of the rebel leader Ronnie Brunswijk.

Both artists bring up ideas about how or why we should remember in ways that are circumspect about nationhood’s promises. They bring up issues about the relationship between art and local politics in a fragile democracy. They take this on in an era very different from that of Waka Tjopu, for example, a moment traditionally associated with political engagement and the social value of visual production. A time when terms like “struggle” and “progressive” had a particular charge.

For Pinas and Nahar, these investigative works fuse ideas of personal and collective interests reaching beyond the immediate moment or place. They seek to interrogate the purpose of visual production and the strategies of articulating the challenges of contemporary Caribbean society. As a Ndjuka, Pinas has been articulating presence and visibility throughout his entire career by highlighting the visual language, culture, and social challenges of his community. Nahar, from an urban “creole” backgound, has incorporated this event into his practice. Through the dissonance of associative random fragments on the surface of his collages, he assembles an alternate view of our reality by abandoning the rational to rearrange and re-see. His ongoing interrogative stance and process collides with or arrives at this current political moment.

Optimistically and confidently, both artists test out the boundaries of visual and political propriety by referring to these events. It is counter-politics to the manufacture of fear by insecure aggressive regimes. The December Killings were intended to erase opposition while strategically inserting violated ghosts into the daily imagination of the political class. It generated silence while asserting itself into everyday consciousness. Nahar has worked with and around this once unmentionable moment, re-conjuring it to alter the value of how it resides in our memories.

The vengeful acts of Moiwana were aimed at a particular community then residing outside the coastal political embrace that stood in for what is politically called Suriname. Pinas has built a large-scale monument on the actual site in a forceful declarative manner. It is a site for personal rememberance of lost friends and relatives, for ethnic and national reflection, and also an aesthetic/experiential artistic site-specific-work.

Both artists list names and events in their projects. One gesture is temporal, hoping to trigger memory, undermine silence, and generate debate. The other is a permanent structure, monumental in scale, creating a new mapping of social history — a new site for all of us from the wider region to visit and to experience. The Afaka characters on the Moiwana monument (Kibii wi — “protect us”) refer to community and protection. They ask the rest of us why can’t we just live together. This is not a challenge in Suriname alone.

Marcel Pinas at his Moiwana monument; photo by Christopher Cozier

Both of these works talk about very recent and current experiences, events that are still raw and unresolved within living memory. They acknowledge and construct another narrative about the region by rethinking nation/culture and its construction. These gestures have to be seen within the wider narrative of the Caribbean’s social and political history, and also at the boundary of where it meets with that of South America. These works are aimed at political futures. Another election is coming, and the various players of these moments are still alive and among us. The artists want us to remember, but also to imagine a future that can resolve and transform the meaning and the value of these moments.

Kurt Nahar’s 8 Dec 1982 installation at Fort Zeelandia; photo by Christopher Cozier

Nahar’s “agitational” mode jettison aesthetic concerns and consciously aims to be caustic — even obnoxious. The way the work is put together expresses an unease, discomfort, and even anger — it seems to be about denying pleasure. One minor concern could be the political implications of the commodification of the December Killings and the expedient usage of the event within electoral politics by interest groups and registered parties. Some have speculated that Nahar’s ongoing concern may also begin to condense the meaning and the possible value of the revolutionary in our historical narrative, and may then obscure what was otherwise accomplished and that may remain unresolved on the road out of colonialism.

Nahar is expressing his concern for the future of his country through highlighting one of its darkest and most challenging moments. He is asking how we can move forward from these unresolved moments. It is a feeling shared throughout the Caribbean, as during the 1980s a number of horrific acts of violence haunted our revolutionary movements and remain with us mostly in popular music, poetry, marginal academic texts, and now more and more through the visual.

Nahar’s strategic lack of composure becomes his way of expressing rage and outrage. The objects are roughly put together, and talk about fragmentation and disharmony and anxiety. Is he asserting that nothing beautiful can come of or from this moment, especially if it remains suppressed and virulent? The work expresses a grasping or gasping — an outburst from a prolonged silence. Unlike the works of previous generations, Nahar is not declaring or invoking an ideal — he is rubbing the lamp, acknowledging a festering reality.

Scattered between the trees around the Fort, which he refers to as “silent witnesses”, bright red posters with the bold initials of the assassinated individuals were nailed to their trunks like sacrificial figures. They looked like standard cheap election posters with their inelegant typography, but instead of smiling, promising faces and catchphrases we got lines of poetry and then just initials. The jarring red tone suggests the violence and the bloodletting of the early 80s as ideological engines, local and internationalist struggles began to simmer. I think of Grenada, Guyana, Trinidad, and Jamaica, as well as other parts of the continent. The internal struggles and the official reactions from Greenbay to Lopinot still haunt us. The heady brew of revolutionary rhetoric and dew breakers, hit squads acting with impunity to maintain the status quo or the Revo from the north to the south of Reagan’s back garden, what was called the Caribbean Basin, are all conjured.

How does a new generation deal with this odd and rapacious Oedipal mask? Does this work then betray the “value” of this revolutionary moment — limit or interrupt its passage into memory and understanding by overstating its darker manifestations, as it allegedly defended its process? Does it highlight the blood-thirsty rationalizations of its imposed optimism and unfulfilled promises?

One can say that the work does not ask about the past as much as it asks about the current moment and the future we are in the process of making — or, as some thinkers suggest, the past imagined futures in which we now reside. That these kinds of political artistic statements can be made now, in Paramaribo, asks an important question about the current state of Surinamese democracy. Will this moment last beyond the outcome of the next election? It also asks about the degree to which artistic expression is seen as agentive or as a large enough social concern. Is it seen as persuasive? It questions the troublesome and vicarious relationship with us, the curators, critics, and exchange artists, with foreign passports and return flights.

Marcel Pinas visiting his Moiwana monument; photo by Christopher Cozier

Pinas’s monument is also operating in this space of questioning. His calm and more composed spatial work looks towards creating an awareness of a newer, more current and pressing question. Ironically, the “creole” nationalist regimes of the region create monuments to rebellion and Emancipation and some even use Maroon culture to symbolise national and cultural resistance within these narratives. Regional monuments speak about the negotiated moment and the gift of freedom towards citizenship for owned entities, ex-slaves but still subjects of the various Crowns within the engine of Modernity.

Cuffy (in Guyana) rages as a primal mystical force, Makandal (in Haiti) blows his shell, Bussa (in Barbados) shakes his fist at the sky (with nice shorts). Two naked and pre-Black statues look at each other not yet aroused in Kingston, like the first steps after the customary drum roll of a Carifesta choreography. And so it goes. Pinas’s work declares a space for thinking, for reflection, rather than objectifying or caricaturing. Is there a way that these officially installed objects obscure or silence unresolved questions about the transformation we hurriedly celebrate in the Post-Independence space?

But the Moiwana monument asks a question or declares an intention about shared space and community. This is not a narrative of subjected fusion, but one about each cultural self remaining intact while connecting and communicating. The work also ventures into inscribing new regional monuments or moments for reflection — new sites of memory and commemoration.

So this gesture is both a personal and a community concern, national and transnational. It recognises those made absent not just in the massacre but in the social dynamics of the country itself. It speaks not just to Suriname but through its scale to all humanity when we falter. Recent events in Albina indicate the fragility of these relations, and the resentments shaped by a long history of neglect.

Marcel Pinas’s Moiwana monument; photos by Christopher Cozier

Pinas’s rising object with Afaka signs surrounded by smaller metal and concrete tablets inscribed with the names of those killed sits in a forest clearing. It is always seen against the sky or the heavens, accordingly. The sound of the wind and the sound and feel of the sharp chipped stone fragments under one’s feet create a harsh effect as you walk around the clearing looking at the names. The sound of the gravel makes one keenly aware of one’s individual presence at this site, and also one’s vulnerability. The meeting point of metal, concrete, and stone rising out of the forest clearing creates a sombre tone, as one tries to conjure the moment in a small rural village setting. Again the trees in the forest are like silent witnesses surrounding the site.

The state has recognised these injustices and investigations, and court cases continue while the artists process these memories and feelings. The artists are not seeking justice or retribution, but to excavate these memories for illumination and reconciliation. Ultimately, Pinas and Nahar seek to alter the emotional and political value of these moments.

Postscript:

While writing this note, I saw a series of images by photographer Harvey Lisse, posted on Facebook. Titled “Black Beauties”, the photos simply use Fort Zeelandia as a backdrop or texture to capture the beauty and lightheartedness of a young Surinamese woman. It’s a glamour series, the stereotypical kind of images that young guys with cameras take of beautiful young women. The urban cool of the era of Vibe magazine is conjured. Even though conventional in terms of how women may traditionally reside within the frame, some of the images take in a non-conventional implication when one thinks of the chosen location. In an image called “against the wall”, a young woman leans against the wall of the fort looking back at the viewer. One has to stop and wonder: is the artist winking or just oblivious? Either is critically interesting, as a vantage point or step along the way from previous readings of the site. In these images, the black body or self is not a violated presence but a celebrated one. In this way, Lisse’s images may be heading to yet another reading of the site, taking us one step further as two historical moments, a colonial fort and a postcolonial dungeon, become merely the backdrop for another creative moment.